Programming With Types (Part 1)

One of the book I’ve read recently is called Programming With Types from Vlad Riscutia published by Manning Publications.

I happened to purchase a bundle from Humble Bundle a while ago and I thought it was a good time to read it to strengthen my knowledge on Javascript Typescript (as used as examples in the books).

On this post, I will summarize the keys content of the book. I recommend you buy the book to read on for more details.

Chapter 1: Introduction to Typing

This chapter basically defines some terminologies regarding to the Typing system. These can be summarized as the followings:

A type is a classification of data that defines the operations that can be done on that data, the meaning of the data, and the set of allowed values. Typing is checked by the compiler and/or run time to ensure the integrity of the data, enforce access restrictions, and interpret the data as meant by the developer.

A type system is a set of rules that assigns and enforces types to elements of a programming language. These elements can be variables, functions, and other higher-level constructs.

The process of type checking ensures that the rules of the type system are respected by the program. This type checking is done by the compiler when converting the code or by the run time while executing the code.

The component of the compiler that handles enforcement of the typing rules is called a type checker. If type checking fails, meaning that the rules of the type system are not respected by the program, we end up with a failure to compile error or with a run-time error.

Benefits of type system:

-

Correctness: Correct code means code that behaves according to its specification, producing expected results without creating run-time errors or crashes. Types help us add more strictness to the code to ensure that it behaves correctly.

-

Immutability is another property closely related to viewing our running system as moving through its state space. When we are in a known-good state, if we can keep parts of that state from changing, we reduce the possibility of errors.

-

Encapsulation is the ability to hide some of the internals of our code, be it a function, a class, or a module.

-

Having the ability to combine independent components yields a modular system and less code to maintain. Composability becomes important as the size of the code and the number of components increase

-

Readability: Instead of having to find the implementation or look up the documentation, just reading this declaration tells us exactly what type of arguments to pass and reduces our cognitive load, as we can treat it as a self-contained, separate entity.

With static typing, type checking is performed at compile time, so when compilation is done, the run-time values are guaranteed to have correct types. Dynamic typing, on the other hand, defers type checking to the run time, so type mismatches become run-time errors.

Strong typing and weak typing. JavaScript is weakly typed. JavaScript provides two equality operators: ==, which checks whether two values are equal, and ===, which checks both that the values and the type of the values are equal

Type inference: In some cases, the compiler can infer the type of a variable or a function without us having to specify it explicitly.

Chapter 2: Basic types

This chapter will look at some of the commonly available primitive types (empty, unit, Booleans, numbers, strings, arrays, and references), their uses, and common pitfalls to be aware of

Designing functions that don’t return values

-

An empty type is a type that cannot have any value: its set of possible values is the empty set. We can never instantiate a variable of such a type. If a function, let’s say its name is

raised()then it’s never meant to return. if someone accidentally updates the function later and makes it return, the code no longer compiles. -

A function might not return for several reasons: it might throw an exception on all code paths, it might loop forever, or it might crash the program.

-

A unit type is a type that has only one possible value. If we have a variable of such a type, there is no point in checking its value; it can only be the one value. We use unit types when the result of a function is not meaningful.

-

Functions that take any number of arguments but don’t return any meaningful value are also called actions or consumers.

Boolean logic and short circuits

-

The canonical two-valued type, available in most programming languages, is the Boolean type. Some type systems provide Booleans as a built-in type with values true and false. Other systems rely on numbers, considering 0 to mean false and any other number to mean true. TypeScript has a built-in boolean type with possible values true and false.

-

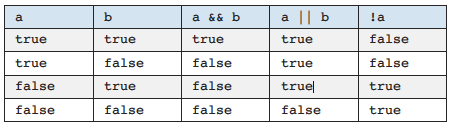

Many programming languages use the following symbols for common Boolean operations: && for AND, || for OR, and ! for NOT. Boolean expressions are usually described with truth tables

-

Short circuit evaluation

a. Most compilers and run times perform an optimization called short circuit for Boolean expressions. Expressions of the form

a AND bare translated toif a then b else falseb. So for example, let’s say we have a function which checks for a Post comment like the followings:

function allowPost(comment: string, userId: string): boolean { if ((comment == "") || (secondsSinceLastComment(userId) < 10)) }

c. If the first operand is true, the second operand will be skipped and hence the expensive functionsecondsSinceLastCommentwill not be run. We prefer ordering conditions from cheapest to most expensive.

Common pitfalls of numerical types

-

The width is the number of bits used to represent a value. This can range from 8 bits (a byte) or even 1 bit up to 64 bits or more. Bit widths have a lot to do with the underlying chip architecture: a 64-bit CPU has 64-bit registers, thus allowing extremely fast operations on 64-bit values. There are three common ways to encode numbers of a given width: unsigned binary, two’s complement, and IEEE 754.

-

Integer types and overflow

a. An unsigned binary encoding uses every bit to represent part of the value. A 4-bit unsigned integer, for example, can represent any value from 0 to 15. In general, an N-bit unsigned integer can represent values from 0 (all bits are 0) up to $2^N$-1 (all bits are 1)

b. If we also want to represent negative numbers, we need a different encoding, which is usually two’s complement. In two’s complement encoding, we reserve a bit to encode the sign. Positive numbers are represented exactly as before, whereas negative numbers are encoded by subtracting their absolute value from 2N, where N is the number of bits.

-

What if we are using a 4-bit unsigned encoding and try to add 10 + 10, even though the maximum value we can represent in 4 bits is 15? Such a situation is called an arithmetic overflow. The opposite situation, in which we end up with a number that is too small to represent, is called an arithmetic underflow.

a. Wrap around is what the hardware usually does, as it simply discards the bits that don’t fit. For example, if we adding 1 to

1111, the result would be10000but then because we only have 4 bits, it would be0000(1 is discarded).b. Saturation is another way to handle overflow. If the result of an operation exceeds the maximum representable value, we simply stop at the maximum.

c. The third possibility, error out, is to throw an error when an overflow happens

Floating-point types and rounding

-

In TypeScript (and JavaScript), numbers are represented as 64-bit floating-point using the binary64 encoding.

-

The three components of a floating-point number are the sign, the exponent, and the mantissa. The sign is a single bit that is 0 for positive numbers or 1 for negative numbers. The mantissa is a fraction as described by the formula in figure 2.2. This fraction is multiplied by 2 raised to the biased exponent.

-

Because of rounding, it’s usually not a good idea to compare floating point numbers for equality. Instead, javascript provides a value as

Number.EPSILONfor comparing whether the values are within the threshold. - This is example:

function epsilonEqual(a: number, b: number): boolean { return Math.abs(a - b) <= Number.EPSILON; } console.log(0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 == 0.3); console.log(epsilonEqual(0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1, 0.3)); - Most languages have libraries that provide arbitrarily large numbers. These types extend their width to as many bits as needed to represent any value. An arbitrarily large

BigInttype is currently proposed for standardization for JavaScript.

Encoding text

-

String is a primitive type representing text. In early days, computers had at most 256 characters available to represent text. With the standardization of Unicode, which aims to provide a way to represent all the world’s alphabets and other characters (such as emojis), 256 characters obviously are not enough.

-

A glyph is a particular representation of a character. “C” (bold) and “C ” (italic) are two different visual renderings of the character “C”.

-

A grapheme is an indivisible unit, which would lose its meaning if it were split into components, such as the woman police-officer example. A grapheme can be represented by various glyphs

-

When rendering text, we work with graphemes, and we don’t want to break apart a multiple-character grapheme. When encoding text, we work with characters.

-

(In order to understand more about this chapter, I recommend to take a look at section 2.4 Encoding Text on the book)

Building data structures with arrays and references

-

Arrays and references are two last common primitive types

-

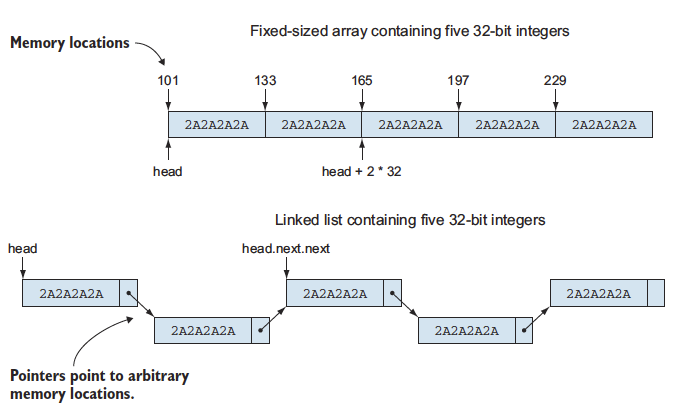

Fixed-size arrays store several values of a given type one after the other, enabling efficient access. Reference types allow us to split a data structure across multiple locations by having components reference other components.

-

Fixed-size arrays represent a contiguous range of memory that contains several values of the same type. An array of five 32-bit integers, for example, is a range of 160 bits (5 * 32) in which the first 32 bits store the first number, the second 32 bits store the next, and so on.

-

Arrays are commonly used compared to the opposed alternative, linked list, as it’s fast to access due to the space allocated continuously.

-

Reference types hold pointers to objects. The value of a reference type—the actual bits of a variable—do not represent the content of an object, but where the object can be found

Binary trees

-

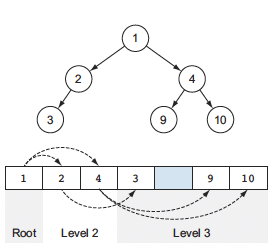

Let’s look at another type of data structure in which we can append items in multiple places called Binary tree.

-

One option is to represent a binary tree as an array. The first level of the tree, the root, has at most one node. The second level of the tree has at most two nodes: the children of the root. The third level has at most four nodes: the children of the previous two nodes and so on

-

This is not very efficient as the array has fixed size and as the tree is growing, we need to allocate space, such as doubling size, to make room for all the possible new nodes.

-

Because of the extra-space overhead, binary trees are usually represented with a more compact representation using references. A node stores a value and references to its children.